Have you ever posed the question of how a disease or illness develops?

The pathogenesis – where the illness comes from, the trajectory it takes, the consequences it brings – is well-researched and is focused on in the medical world, as well as treatments that are focused on putting the body back together to its original, allegedly healthy state.

What many patients and doctors fail to see, however, is that there is another question that could be asked:

How does health develop? Where does health originate? What are causes of well-being?

This is what Salutogenesis is trying to answer. Let’s take a look at the findings so far.

A small disclaimer right at the beginning: the field of salutogenic research is spread pretty far. There are different definitions and ways of looking at salutogenesis and understanding it in general. Sometimes it is meant as an umbrella term, sometimes it is equaled to the Salutogenic Theory. We use the term and its topics within in such a way that cancer patients find something actionable to do when presented with this model and theory. We have linked different topics within Salutogenesis and have excluded some other research or focal points.

Nevertheless, asking the salutogenic question and understanding that there is something to work towards, is what is important and useful.

The what and how and who?

Salutogenesis and the research of it goes back to Aaron Antonovsky, an Isreali-American medical sociologist. In talking to concentration camp survivors, he found it curious that some survivors were able to live long and rather happy lives after their traumatic experiences, while others with the same experiences, died soon after their liberation. He thus looked at the connection between health, coping and stress factors.

We have taken two aspects of his work that we feel like serve us and cancer patients well in becoming more aware of what constitutes health.

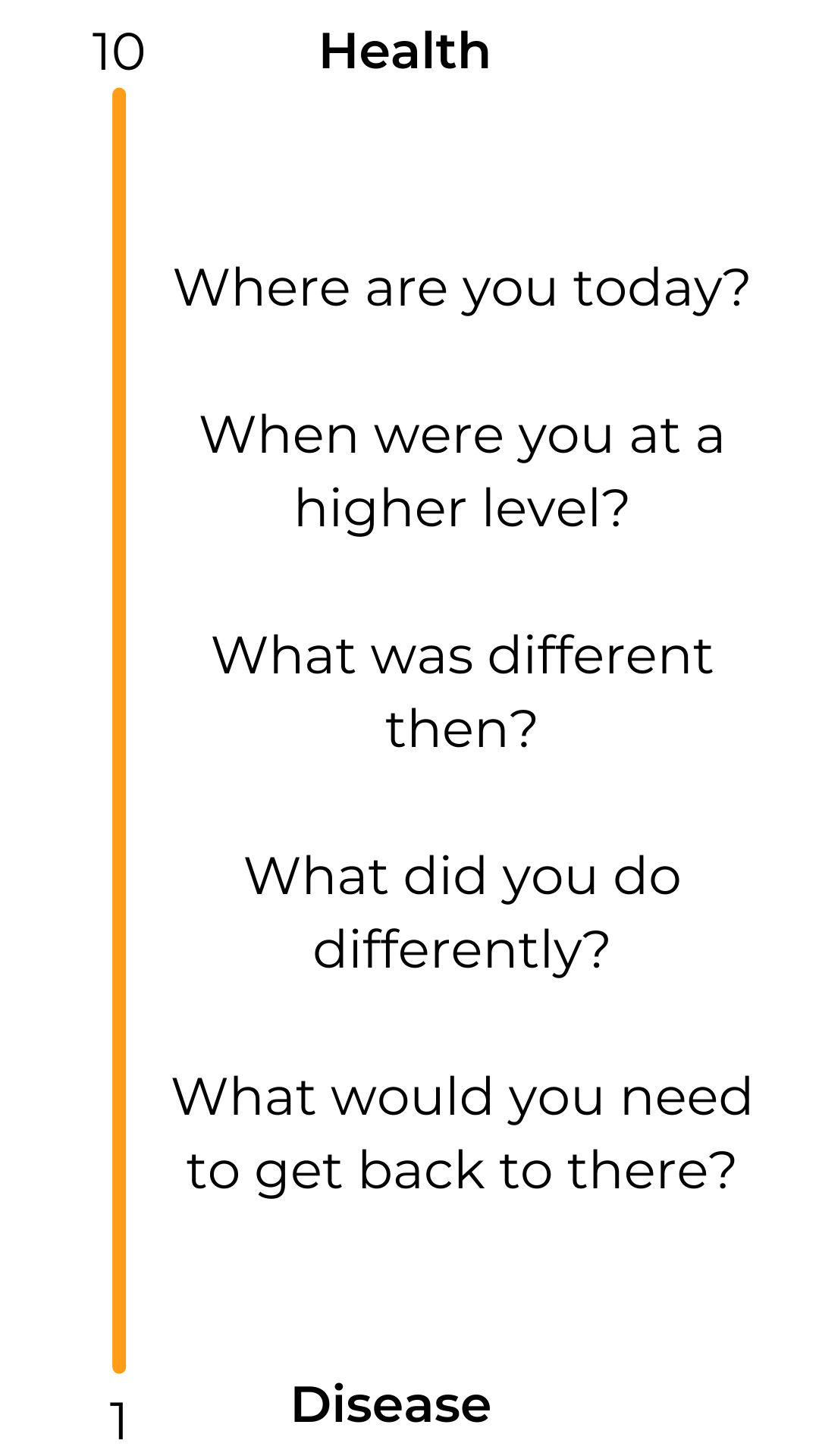

Health-ease vs. dis-ease continuum

The first aspect is that Antonovsky rejects the dichotomy of health and illness. Rather, he describes the relationship between health and illness as the “health-ease versus dis-ease continuum”. In other words, the two states of health and illness are opposite poles on a continuum, but they are not mutually exclusive. That means, you are not either sick or healthy, but you are somewhere on the axis between the poles of the continuum. And this place on the spectrum can change from day to day. That means that if you are sick, there are still healthy elements that can help you overcome the illness.

Recognizing that there are always healthy parts within you is a great step forward in working with cancer patients or anyone that is dealing with a disease. Because it allows you to take action towards strengthening the healthy parts.

Working with the Continuum

You could ask yourself, for example, where you are on a scale of 1 to 10 (1 being entirely ill, 10 being entirely healthy). If you’re at a 3 today, where were you yesterday? Was there a time when you were at an 8? What did you do differently then? How could you get back to it?

The awareness and idea alone are often a good starting point for clients to begin analyzing and recognizing their own power over the outcome. The comparisons make it clear that everything is changing and can vary even from day to day. And it is also about recognizing that whatever decision you make, however you behave has an influence on your well-being and your health. The continuum aids us in putting the focus and the goals towards the higher end of the scale and breaking down steps towards reaching that number 8.

So how would you do this if not with the medical cancer treatment and therapies?

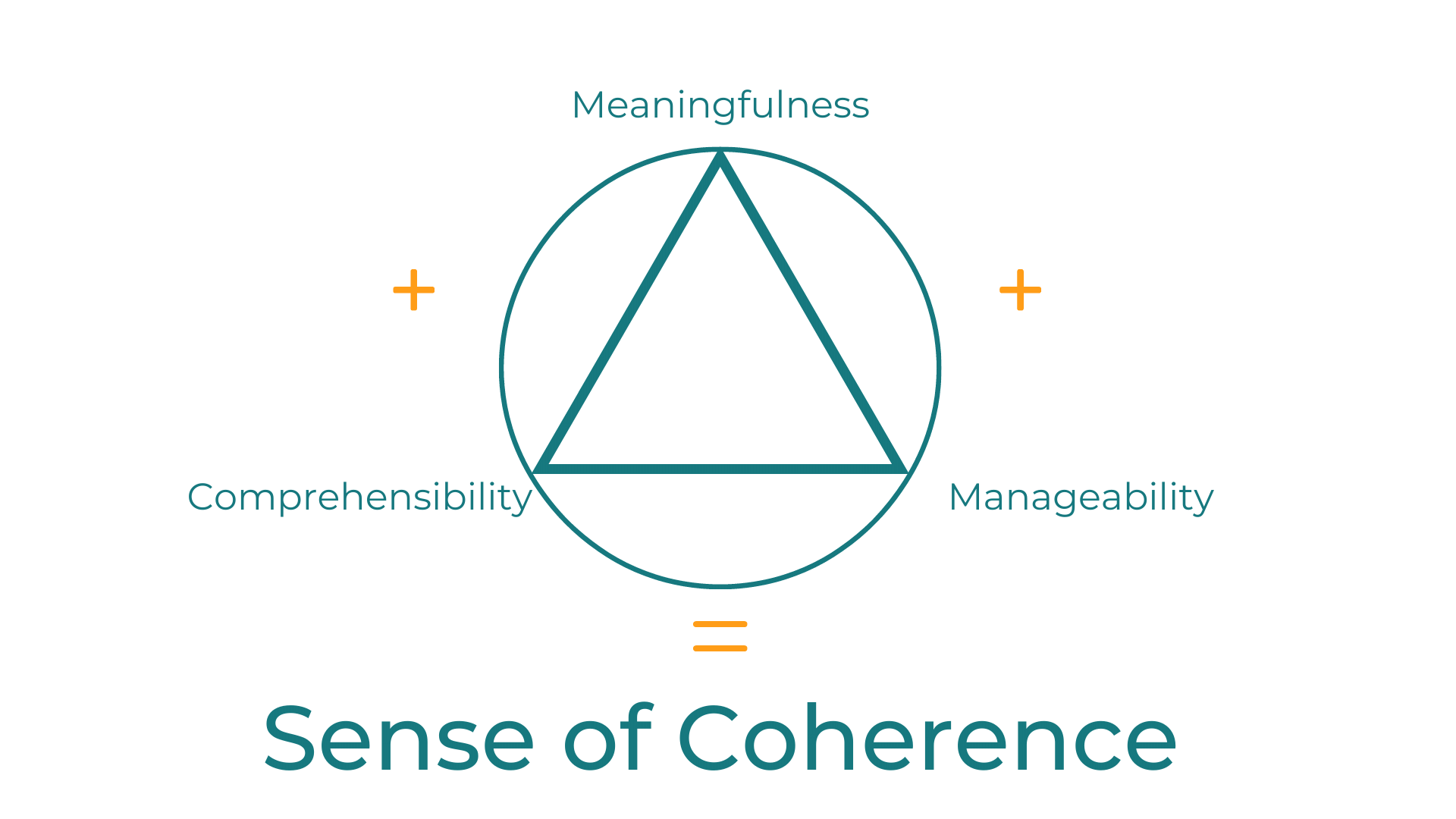

This is where the second aspect comes in: The Salutogenic Theory or the Sense of Coherence.

As part of a more general study into the potential links between stress, health and coping, Antonovsky talked with holocaust survivors. As mentioned before, he discovered that some of these survivors, despite experiencing the cruel, tragic and traumatic life in concentration camps, were able to thrive in later life, were successful in what they set out to do after being rescued from the camps, while others with very similar experiences died very early after their rescue.

Antonovsky realised that these successful survivors must have had some powerful factors that enabled them to cope with their experiences in such a way that their mental well-being and health was not impaired to the extent that a return to a normal life was no longer possible.

There are three factors responsible for coping with life’s stressful situations in a healthy way:

Comprehensibility

or having a sense of understanding as to how your life evolved in an orderly, predictable and explicable fashion, which in turn allows you to understand how hardships or stress situations in your life came to be. This awareness might make it easier to accept these stressors and to project this understanding into the future

Manageability

or the belief that you have the skills and resources to deal with and manage the stress or hardship. That you can take actionable and controllable steps and that in consequence you are not a victim of your circumstances

Meaningfulness

is the most important one. It is the belief that life is inherently interesting, satisfactory, fulfilling and worthwhile. That there is a good reason or purpose to care about what happens at any given time and to see life’s situations as a welcome challenge instead of a burden

Combined, these three factors make up the Sense of Coherence. You might know that feeling where everything feels just right, perfectly aligned and harmonious. It is easy to imagine that having a great sense of coherence makes it easier to deal with life’s challenges in a constructive and positive way.

Applying the knowledge of Salutogenesis

So now that we know aspects of health’s origin, what do we do with that knowledge?

In order to develop a good sense of coherence, comprehensibility, manageability and meaningfulness need to be strengthened. When applying this to a cancer disease, the following questions and ideas might help to dive a little deeper into the three factors.

First of all, a cancer patient should try to understand or comprehend his or her own illness. These questions demand an answer:

- What is happening in my body? Where or why is it trying to attract my attention?

- At which points in my life did I not pay enough attention to myself and my body?

- Where did I exceed limits and put too much (stress, responsibility, burden, …) on myself?

Secondly, it is about the manageability of the disease, so:

- What exactly can I do now to optimize my recovery process?

- Which therapies will be part of my treatment plan?

- Am I looking beyond classical medicine and want to make use of naturopathic alternatives?

Manageability is an important part in recovery because it is an essential step towards taking action, being in control and therefore not falling victim to the situation.

And thirdly it is important to find or re-define meaningfulness in one’s own life. Meaningfulness doesn’t have to be an answer to the big “what is the meaning of life” question. Small things can be very meaningful as well. It is rather about seeing and experiencing life as interesting and worth living. To recognize that being alone is also meaningful.

These questions could be helpful in finding meaningfulness:

- What goals do I have for my life?

- Where is life interesting to me? What is fascinating about life?

- Which daily activities and occurrences make me happy and content?

- What insights did I gain from my disease?

Finding that Sense of Coherence or even just working with one of these factors is a way of creating a more positive outlook on life. And that in turn will help you along the axis of the continuum.

Sometimes it easier to go through these questions with help from the outside. Someone impartial, that is more of a guiding hand towards finding answers and re-inviting the Sense of Coherence into one’s life. If you’re having trouble finding the strength and maybe honesty to work on this by yourself, consider asking a partner, friend or a cancer coach to help guide you through this.

Tell us how you fare with these ideas and whether you’ve heard of the Salutogenic Model before!

You can also watch our free preview lesson on salutogenesis in our training course “Become a (Psycho-Oncological) Cancer Coach” here.

More information on the course itself: Click here.

All the best,

Your TBAcare Team

![]()